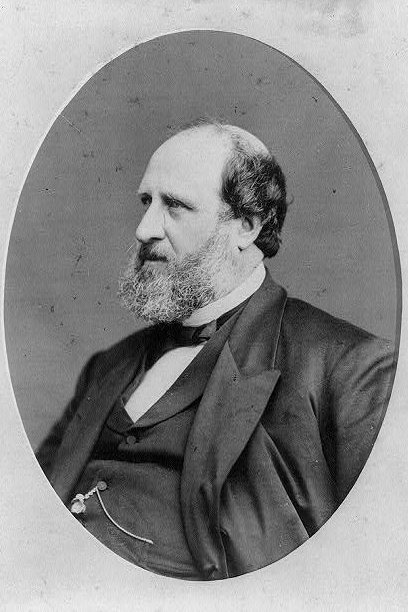

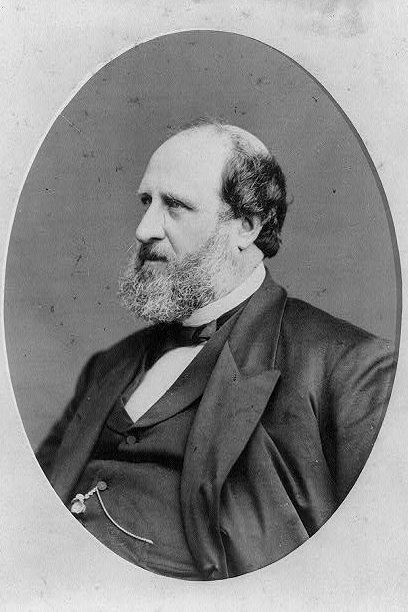

One hundred and fifty years before Rep. George Santos was charged with a host of financial crimes, a former New York congressman, William Magear “Boss” Tweed, sat in one of the city’s courtroom docks. Tweed was facing 55 charges of embezzlement of public funds, with each offense involving multiple counts.

When the jury found him guilty in November 1873, it was of 102 separate crimes, for which prosecutors pursued a 102-year sentence.

So many individual verdicts had to be returned that, as Kenneth D. Ackerman wrote in his biography “Boss Tweed: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York,” the jury foreman had to hand the clerk a written formula to break down the specific items of the indictment. The conviction only added to the scandal that had engulfed Tweed, an enormously influential power broker in 19th-century New York.

But, despite those 102 counts, Tweed would make it out of prison soon enough, only to be jailed again — and then dramatically escape.

It had all started with humble beginnings. Born on Cherry Street in today’s Lower East Side, Tweed left school at age 11 to work in his family’s furniture-making business. As a young man, he joined the Americus “Big Six” volunteer fire company, infamous for decorating its pump wagon with tiger artwork and brawling with rivals when responding to blazes.

Elected as the crew’s foreman, the rotund, towering Tweed soon was approached by the Society of St. Tammany, otherwise known as Tammany Hall, the private group and Democratic political machine that provided shelter, jobs and food to New York’s flow of immigrants.

After declining Tammany’s first request for him to run as alderman on its behalf, Tweed accepted in 1851. He had witnessed vote-buying on the streets of New York during the 1844 presidential election, and decided to put his bookkeeping skills — taught to him by his father while working in his store — to good use.

Tweed was elected alderman for the Seventh Ward in New York in 1851 and won election to the House of Representatives the next year. Though he failed in his House reelection bid, by 1856 he had been elected as school commissioner, then a member of the New York County Board of Supervisors, before he was elected to the state Senate in 1867.

Tweed’s soaring popularity was no accident: He had capitalized on the city’s immigrant communities by selling citizenship documents, issued via complicit local judges, in return for a pledge to vote for him. By 1863, he was exempting workmen, police and fire crews from Civil War conscription or paying the $300 commutation clause.

His power soon grew further. In 1870, Tweed marshaled the Democratic majorities in the state legislature to usher in a new charter, one that specifically altered the governing structure of New York City and gave local representatives more autonomy over political appointments. Tweed thereafter installed friends into powerful positions, many of whom championed his industrious public image and civic achievements.

As a result, he became a recorded sponsor in the building of Central Park Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Upper West Side, the American Museum of Natural History and the Brooklyn Bridge. With the power to preside over construction contracts, he skimmed money — 15 to 35 percent — from city development works via his board of supervisors.

The former congressman’s cronies lined his and their pockets, too. Together, the Tweed Ring bribed, raided and re-appropriated millions of dollars from New York’s budget via falsified leases, inflated service prices and goods purchased from co-conspirators. Selected companies would deliberately carry out substandard building work that soon required repairs — which other bidders hooked into the Tweed Ring would handle.

One operation involved stalling the construction of New York’s pneumatic transit system, a precursor to today’s subway. Tweed was a major stakeholder in the streetcar and omnibus lines, and he viewed the potential new alternative as a threat to his income.

As Tweed’s grip on the city grew, his corruption became increasingly flagrant. Soon, a reform movement grew in opposition to his plundering.

Three of its more prominent voices calling for his imprisonment were New York Times publisher George Jones; the prominent reform lawyer Samuel J. Tilden; and Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast. Ignoring bribes of $100,000 by Tweed’s representatives to leave his subject alone, Nast depicted Tweed variously as an obese grotesque with a sack of dollars for a head and as a giant standing next to a ballot box proclaiming, “As long as I count the votes, what are you going to do about it?”

The sketches incensed Tweed, who is alleged to have remarked, “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care so much what the papers say about me — my constituents don’t know how to read — but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!”

The cartoons helped force officials into action. County Sheriff James O’Brien, a former Tweed ally who since had tried and failed to blackmail him, leaked details of the ring’s illegalities to Jones and the Times.

With enough evidence for charges of larceny and forgery, Tweed was arrested and convicted of those 102 crimes. But an impassioned plea from his defense helped lower the total punishment to 12 years in prison. A higher court reduced it further, to just 12 months.

Tweed spent those 12 months with such luxuries as a springboard mattress, a velvet sofa and library books in his cell. But the state, while Tweed was behind bars, sought to recover some of his embezzled money by filing a $6 million lawsuit against him. The suit resulted in his rearrest and sentencing to the Ludlow Street debtors’ jail in 1875.

Tweed, though, was allowed home visits to relatives, under escort by a jailer. And while he was visiting his son’s brownstone on Madison Avenue, on the pretext of speaking with his sick wife, he slipped away while William Jr. and the warden waited downstairs.

Tweed had planned to escape via a covered wagon; a mark drawn on the stoop at his son’s front door was his signal that his jailbreak was due to go ahead. Catching a boat in the Hudson River to New Jersey, and traveling with a red wig and spectacles under the alias “John Secor,” Tweed journeyed on to Cuba, a country with no extradition treaty with the United States.

After he was recognized by the American consul in Havana, Tweed crossed the Atlantic to Spain. But New York officials sent one of his cartoon depictions to the Spanish port authorities, who identified the former congressman despite his posing as a seaman, and despite his considerable weight loss caused by seasickness.

After a brief detention in Spain, Tweed was returned to Ludlow Street via the USS Franklin frigate on Nov. 23, 1876. He tried to broker an early release by disclosing details of his illegalities to a board of aldermen investigative committee. Tilden — by then the governor of New York — ensured the deal was not honored. The convicted congressman died of pneumonia while incarcerated on April 12, 1878.

Tweed since has become synonymous with political corruption and unchecked greed, appearing both in novels and as a side character in Martin Scorsese’s 2002 crime epic “Gangs of New York.” In a final twist, the politician brought down by a newspaper cartoon was in 2009 mourned by the New York Post, which ran a tongue-in-cheek op-ed pining for his return. “It’s midnight in our politics,” it read. “The state has been cleansed of giants.”

A week before, coincidentally, former congressman William J. Jefferson (D-La.) received 13 years’ imprisonment, having been found guilty of 11 counts of corruption.

It was an incarceration that set a congressional record, beating Boss Tweed’s sentence by a year.

Comments are closed.