President Biden on Friday expansively praised the rocky, 11th-hour passage of legislation to suspend the debt ceiling, cut federal spending and avoid a government default, claiming victory for the bipartisan philosophy that is likely to be central to his reelection argument.

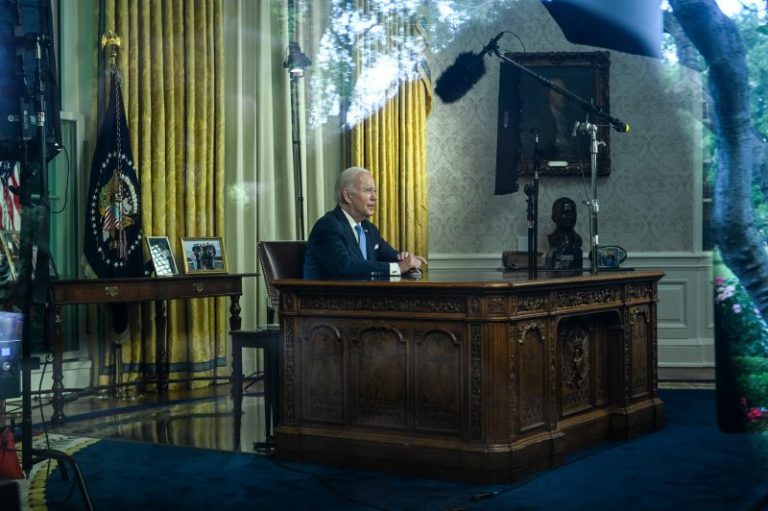

Speaking from the Oval Office in a 13-minute address, Biden said the nation had narrowly avoided economic catastrophe and that the wide-ranging agenda he had pushed through during his first two years in office would not be derailed.

“Passing this budget agreement was critical. The stakes could not have been higher,” Biden said. “No one got everything they wanted, but the American people got what they needed. We averted an economic crisis and an economic collapse.”

Biden said he would sign the bill Saturday, after the House and Senate complete the technical actions needed to send the legislation to his desk.

“When I ran for president, I was told the days of bipartisanship were over, that Democrats and Republicans could no longer work together,” Biden said. “But I refused to believe that, because America can never give in to that way of thinking. The only way American democracy can function is through compromise and consensus, and that’s what I’ve worked to do as president.”

Friday’s speech, and the signing event a day later, will amount to a victory lap, as Biden leans into an argument that is expected to be at the heart of his pitch for a second term: that he is a seasoned, competent leader who is able to deliver results in a fractured Washington and a divided America.

But it was not all bipartisan comity. Biden’s remarks also provided an opening version of the tougher side of his campaign message, including an emphasis on making the wealthy pay more in taxes and a denunciation of those he depicted as radicals on the other side.

“There were extreme voices threatening to take America, for the first time in our 247-year history, into default on our national debt,” Biden said. “Nothing — nothing — would have been more irresponsible. Nothing would have been more catastrophic.”

The passage of the budget agreement had the additional benefit for Biden of postponing any additional debt limit standoffs until after the 2024 election.

Biden is now heading into campaign season with the economy showing resilience, as employers posted 339,000 jobs in May, far more than economists expected. Meanwhile, predictions of chaos engulfing the southern border after the lifting of pandemic-related restrictions have not so far materialized, and Biden’s top Republican rivals are engaging in open warfare against each other.

The debt measure joins other bipartisan bills from Biden’s presidency, including measures that invested in the nation’s infrastructure, bolstered semiconductor manufacturing, addressed gun violence and helped veterans exposed to burn pits in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Debt ceiling deal

End of carousel

Those bills came at a time when Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress, albeit by razor-thin margins. The debt ceiling deal arguably comes amid a more difficult landscape — five months after Republicans took control of the House, leaving Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) to preside over his own narrow majority that includes a significant faction of hard-line conservatives.

Still, Biden, 80, must overcome Republicans’ argument that he is a weak leader at a time when polls suggest voters are concerned about his age. He is already the oldest president in U.S. history and, if reelected, would be 86 at the end of a second term. Several Republican presidential hopefuls have blasted the debt agreement for doing too little to curb spending, with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis saying on “Fox & Friends” that it does nothing to change the fact that “our country will still be careening toward bankruptcy.”

The more immediate political aftermath of the agreement between Biden and McCarthy remains unclear. The deal established that the two party leaders can come together on an urgent issue despite sharp dissents from some in their parties, potentially laying the groundwork for further bipartisan legislation in the McCarthy era.

But McCarthy’s insistence on striking a deal with Biden over the objections of some of his caucus’s most vocal members could also increase pressure on him to defy or confront the president at every turn between now and the election in November 2024.

In his remarks Friday, Biden went out of his way to praise the speaker. “I want to commend Speaker McCarthy,” the president said. “You know, he and I, we and our teams, were able to get along, get things done. We were straightforward with one another, completely honest with one another and respectful with one another. Both sides operated in good faith. Both sides kept their word.”

When the process began, it was far from certain that Biden and McCarthy would be able to raise the debt limit in time to avoid a default.

McCarthy pushed a bill through the House in late April to raise the debt limit through March 2024 at the latest, while capping federal spending for a decade. It was clear the White House would never accept such a proposal — yet some Republicans vowed to accept nothing less.

Conservatives threatened to challenge McCarthy’s speakership if they were dissatisfied with the result, while Biden insisted he would not negotiate on the debt ceiling at all.

But as the “X date” when the government would run out of money approached, each side designated negotiators trusted by the other, and talks began almost around-the-clock. After drawn-out, tortuous negotiations, the result was a plan that each side could call a victory: McCarthy touted its spending cuts, while Biden boasted that it protected his accomplishments.

The Senate approved the debt measure Thursday night on a 63-to-36 vote, allowing Biden just days to sign it before Monday, when the government would no longer be able to pay all of its bills without borrowing more.

The deal, which cleared the House 314 to 117 on Wednesday, suspends the debt ceiling until January 2025. The Congressional Budget Office says the legislation will reduce the deficit by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years.

No one got everything they wanted. Many liberal Democrats opposed the 99-page Fiscal Responsibility Act, objecting to curbs on government spending and to new work requirements for some recipients of federal food stamps and family welfare benefits. Some conservative Republicans also slammed the agreement for not securing more aggressive spending cuts.

Before approving the bill late Thursday, the Senate rejected 11 proposed amendments. Any changes to the legislation would have required it be sent back to the House, making it very difficult to meet the Monday deadline.

To alleviate concerns from Senate hawks that the bill would prevent lawmakers from adequately funding the Pentagon in a crisis, Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) issued a joint statement Thursday saying the “debt ceiling deal does nothing to limit the Senate’s ability to appropriate emergency supplemental funds to ensure our military capabilities are sufficient to deter China, Russia, and our other adversaries.”

In the Senate, Democrats broke 44 to 4 in favor of the bill, while Republicans voted 31 to 17 against it. Among independents, Sens. Angus King of Maine and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona voted yes, while Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont voted no.

Understanding the debt ceiling

1/4

End of carousel

“Democrats are feeling very good tonight,” Schumer said after the vote. “We’ve saved the country from the scourge of default. Even though there were some on the other side who wanted default, who wanted to lead us to default.” In his remarks Friday, Biden listed Democratic priorities he said were protected in the compromise bill: Medicare and Medicaid, veterans’ programs, lower drug prices, climate change initiatives.

McConnell credited House Republicans’ efforts for avoiding a default and curbing “Washington Democrats’ addiction to reckless spending that grows our nation’s debt.”

Still, both leaders may yet have a political price to pay. The most outspoken House conservatives remain furious at McCarthy, saying he gave away his leverage and won few concessions. And some liberals are bitter at the provisions accepted by Biden, including additional work requirements for welfare recipients and easier permitting for fossil fuel projects.

The debt ceiling caps the amount the U.S. government can borrow to fund obligations and commitments it has already made. The existing debt limit was $31.4 trillion, and the Treasury Department had been using what it called “extraordinary measures” since January to shuffle money around in the federal budget to avoid needing to take on more debt.

Biden has said he might eventually seek to declare the nation’s borrowing limit incompatible with the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, which says that the federal government’s debts must be paid.

But for now, Biden sought to bask in the glow of what he portrays as a triumph for his approach to governing.

“I know bipartisanship is hard and unity is hard, but we can never stop trying,” he said in the Oval Office remarks. “Because in a moment like this one, the one we just faced, where the American economy and the world economy is at risk of collapsing, there’s no other way. No matter how tough our politics gets, we need to see each other not as adversaries, but as fellow Americans.”

Leigh Ann Caldwell, Marianne LeVine and Rachel Siegel contributed to this report.

Comments are closed.