Wednesday dawned with another new entrant to the 2024 Republican presidential nominating contest: former vice president Mike Pence.

Pence, students of history will recall, served as vice president to Donald Trump. He mentions this achievement on his campaign website, of course, as follows: “… Vice President Pence’s record of legislative and executive experience, and his strong family values that prompted President Trump to select Mike Pence as his running mate in July 2016. They were elected by the American people on November 8, 2016 and entered office on January 20, 2017.”

And that, as they say, is that. The biography then jumps to February 2021 — after certain unpleasantness that unfolded the month before.

The highly polished video with which Pence made his candidacy official expends no additional energy on the former president. It mentions that he was vice president, but not to whom. Most of it, though, is just the familiar pastiche of stock video clips of Americana, Pence shown near smiling people and news headlines presenting a gloomy picture of the moment. The former vice president’s rhetoric at times competes to be heard over the swelling orchestral score, perhaps an unintentional admission that the latter is more compelling.

Pence is disadvantaged by stepping onto the national stage as Trump’s straight man. No one buys tickets to see the straight man perform alone. Particularly when the straight man refuses to articulate why his solo show will be better.

To strip away the metaphor, that Pence made no actual mention of why he is a better candidate than his former boss is an obvious failing. He, like others in the race, think that perhaps they can somehow shimmy past Trump in the polls while still patting the former president on the back. In fact, they think they have to do so. And perhaps they’re right.

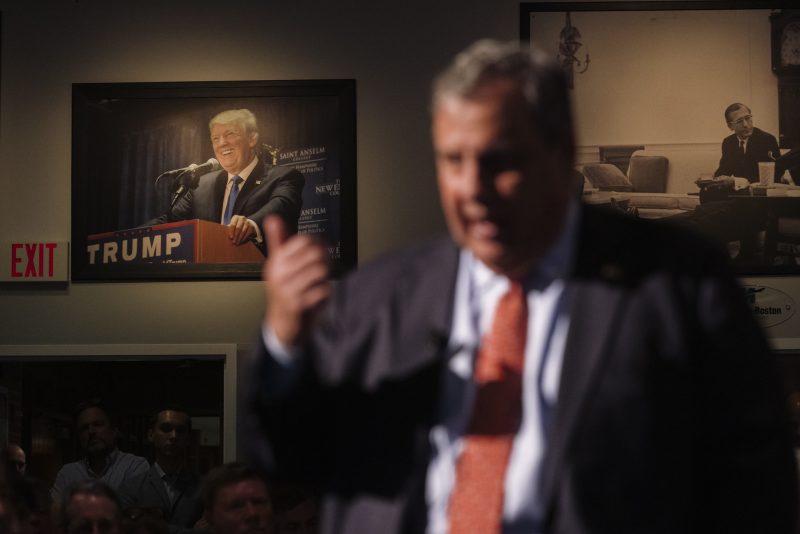

But Pence’s announcement is readily contrasted with former New Jersey governor Chris Christie’s, which unfolded in a town-hall-style event in New Hampshire on Tuesday night.

“Now we have pretenders all around us who want to tell you, ‘Pick me because I’m kind of like what you picked before, but not quite as crazy,’” Christie said at one point. “But I don’t want to say his name because, for these other pretenders, he is — for those of you who read the Harry Potter books — like Voldemort, he is he-who-shall-not-be-named.”

This came just after Christie disparaged one of his opponents by saying that “a lonely, self-consumed, self-serving mirror hog is not a leader.”

Let me be clear, he continued: “The person I am talking about who is obsessed with the mirror, who never admits a mistake, who never admits a fault, and who always finds someone else and something else to blame for whatever goes wrong — but finds every reason to take credit for anything that goes right — is Donald Trump.”

From the top, this was what Christie promised his audience. He leaned into the Jersey shtick, coming out to Bruce Springsteen and assuring the crowd that he’d be willing to throw elbows at his opponents and even challenge them when they had the chance to ask him questions. He said it was something he’d learned when first running in his home state.

“What we found was that people said, yeah, he’s a bully,” he explained. “He’s a bully for us.”

Interestingly, that framing mirrors how Trump frames his own political efforts: He’s taking slings and arrows on behalf of normal Americans. It’s a surprisingly effective argument, one that’s allowed Trump to present things like federal investigations into his retaining documents with classification markings as somehow being about the FBI hating blue-collar retirees.

Christie’s repeated point was that Trump’s actual interest was only in himself.

“Eight years ago,” he said of Trump’s bluster and aggression, “it was amusing. Eight years ago, you were entertained. I forgive you, but it ain’t funny anymore. It’s not amusing anymore. It isn’t entertaining anymore. It is the last throes of a bitter angry man who wants power back for himself, not for you.”

This is objectively true, of course. The lesson of the past eight years should in fact be that Trump’s central focus is on his own retention of power, from his focus on delivering policy victories only for those he viewed as important for winning elections to the post-election period in which his lies about fraud were a vehicle for him to attempt to block Joe Biden’s election.

Christie framed his candidacy as a response to the tendency of Americans to become more insular and their worlds smaller and more comfortable. Trump’s divisiveness, he argued, exacerbated that effect. (He also appeared to ding Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), saying that “we have candidates for president who are talking about issues that are so small that sometimes it’s hard to even understand them.”)

Trump responded to Christie’s mentions of smallness by making fun of the former governor’s girth.

Christie’s dismissals of Trump weren’t limited to his personality. He blamed Trump for the surge in migration at the border, given that Trump had pledged to build a wall that was never completed (much less paid for by Mexico). He criticized Trump’s family, including the multibillion-dollar investment Jared Kushner received from Saudi interests. He compared Trump’s position on Ukraine to disgraced British prime minister Neville Chamberlain. He even accused Trump of lying when he told voters in 2016 that he wouldn’t play golf as president.

There was an unmistakable sense of personal animosity that undergirded the speech, certainly, the sort of thing that has led observers to suggest that Christie’s real intent in a race he’s unlikely to win is to simply do everything in his power to hobble Trump. He had a response to that, as well.

“Christie doesn’t really care about winning. All he cares about doing is destroying Trump,” Christie said. “Now, let me ask you something. How are those two things mutually exclusive?”

“The reason I’m going after Trump is twofold,” he added. “One, he deserves it. And two, it’s the way to win.”

These are the things one has to say when launching a campaign, of course. Christie’s dismissal of the idea that there were “Trump voters” (noting that he, too, had voted for Trump twice) was a bit of transparent gloss on the challenge he faces, as was his noting that Trump was in the single digits himself in mid-2015. What happened after that point was that Trump’s pugilistic style, attacking Republicans and the left equally as he scrambled for power, built a large, sustained, loyal core of support that is a central impediment to Christie’s — and everyone else’s — path forward.

But Christie, unlike his opponents and unlike Trump’s former vice president, is not going to worry about alienating that core.

“It was a mistake in 2016 not to confront Donald Trump early because I knew that so much of what he said was complete baloney,” Christie said in New Hampshire. “… I thought that something that was so apparent to me would be apparent to everybody. Let me guarantee you something: I’m not making that mistake this time.”

That alone sets him apart in this field. But it also likely falls victim to something Christie himself pointed out, that “we always make a mistake politically when we run the next election through the prism of the last one.”

The best time to intervene in Trump’s dishonest, aggressive presentation to voters was, in fact, back in 2016. Now, his core of support has spent eight years building defenses against arguments that Trump lies or is only interested in himself. Trying to convince them that Trump isn’t who they have convinced themselves he is is an enormously difficult task.

To his credit, Christie is at least willing to try.

Comments are closed.